“Don’t Put All Your Eggs in One Basket”

We are all familiar with this sage tidbit of investment wisdom. The undeniable benefits of diversification — or spreading your money over many different investments — are the basis for those popular investment contraptions known as mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Mutual funds and ETFs pool investors’ money in order to purchase many different stocks, bonds, and other investments (some funds own over 1,000 different investments!). Investors can purchase a single share of a fund for less than $50 and have instant, indirect ownership in a wide range of companies, real estate, and bonds — pretty cool!

The Devil is in the Details: Mutual Funds vs. ETFs vs. CEFs

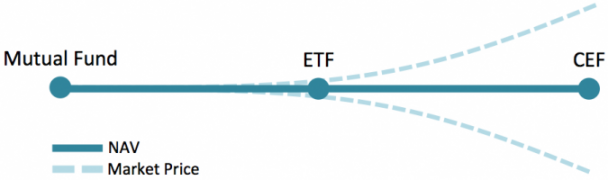

Like mutual funds and ETFs, closed-end funds (CEFs) also pool money from investors in order to buy a portfolio of many different investments. The key difference between each fund type comes down to how and if shares of the fund can be exchanged for a proportionate amount of the stuff in the fund. Before we go any further, let’s discuss a critical concept in the world of fund investing:

Net Asset Value (NAV): The total value of all of the stuff (stocks, bonds, other securities) owned by a fund, divided by the number of shares of the fund. This is also known as the intrinsic value of a share. Most funds publish their NAV daily, and ETFs may publish them on a real-time or near real-time basis.

Mutual Funds

Let’s start by looking at mutual funds, where “what you see is what you get.” When you purchase a share of a mutual fund that has a NAV of $10 per share, you give $10 cash to the mutual fund company to go buy investments with and are issued in return one share of the fund. The share represents $10 worth of assets. If you choose to sell a share of a mutual fund, you present the share to the mutual fund company and receive your little divvy of the stuff in the fund (almost always in the form of cash), which is equivalent to the NAV of the share. Thus, the price of a mutual fund share = NAV per share, whether you’re buying or selling.

ETFs

As we turn our attention to ETFs, the complexity gets amped-up just a little bit. We just learned that with mutual funds, anyone can freely purchase or exchange shares for cash at the NAV price. With ETFs, the rules are a bit stricter: only certain special institutions (like banks) can buy shares from or redeem shares with the ETF company for the NAV price, and they must submit huge orders of shares (often 100,000 share chunks called “baskets”) if they do. For the rest of us peons, we are barred from dealing directly with ETF companies. Instead, we are left to buy and sell shares of ETFs among ourselves, leaving the price of shares to be determined by the forces of supply and demand, and not necessarily what the shares are actually worth based on their NAV.

Although supply and demand in the market determines the price of an ETF share, those aforementioned special institutions can make a quick buck by swooping in and buying up a bunch of shares of an ETF if its price falls much below its NAV, since it can then trade them in to the ETF company for the higher NAV price. Similarly, if the ETF share price rises above its NAV, the institution can buy shares from the fund company at NAV and then make a quick profit by selling them to the public at the higher market price. The lesson here is that this ability for the institutions to make quick little profits if ETF prices drift from NAV actually helps keep ETF prices in the market remarkably close to their actual NAV. (Bonus lesson: being a big financial institution has its privileges!).

CEFs

In the world of closed-end funds, what you see is not necessarily what you get. A fund’s market price and NAV are seldom equal. Here’s why: When a closed-end fund is born, the company that launches the fund sells a certain number of shares to the public in exchange for cash to get the portfolio started. After that, there is no mechanism whatsoever for investors (even special institutions) to redeem shares for NAV or to purchase more shares at NAV. Once the CEF is launched, no more shares can be created or destroyed.

The price of a share of a CEF is set strictly by supply and demand. When demand for a given CEF is strong, investors might be willing to pay more for a share than NAV. In this case, the shares are said to be “trading at a premium [to NAV]”. Conversely, when people are fleeing from a particular CEF, they may choose to sell their shares for less than NAV just to get the heck out of it. These shares are said to be “trading at a discount [to NAV]”. The gyration of CEF prices above and (more often) below their NAVs can potentially be exploited by patient, longer-term oriented, opportunistic investors. More on that to come!

The price of a share of a CEF is set strictly by supply and demand. When demand for a given CEF is strong, investors might be willing to pay more for a share than NAV. In this case, the shares are said to be “trading at a premium [to NAV]”. Conversely, when people are fleeing from a particular CEF, they may choose to sell their shares for less than NAV just to get the heck out of it. These shares are said to be “trading at a discount [to NAV]”. The gyration of CEF prices above and (more often) below their NAVs can potentially be exploited by patient, longer-term oriented, opportunistic investors. More on that to come!